For most Russians, the first four weeks of their country's air war in Syria resembled nothing so much as a high-tech video game. State TV channels showed precision bombs slamming into cockpit-screen targets, while sophisticated computer graphics portrayed areas held by the Islamic State militant group (ISIS) miraculously shrinking thanks to repeated Russian bombing. Until, of course, reality intruded and Metrojet Flight 9268 tumbled from the clear desert sky on October 31, spilling the bodies of 224 middle-class Russian tourists and crew members across 20 miles of the Sinai Peninsula soon after taking off from the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh on the Red Sea.

Thousands of ordinary Russians spontaneously turned out to pay their respects to the victims. In St. Petersburg—where many of the passengers were from—the enormous square in front of the Winter Palace was filled with citizens standing with candles in a vigil for the dead. An exclusive Moscow boarding school offered free places for any children orphaned by the crash. And even the railings in front of the Russian Embassy in Kiev were filled with flowers, toys and candles placed by Ukrainians expressing solidarity with their bereaved neighbors.

"Our media tells us that Ukrainians and Russians should hate each other," posted 19-year-old medical student Oksana Medvedeva under a Twitter photo of her personal floral tribute in Kiev. "But see how hatred kills innocents. We weep with you, brothers and sisters."

As Russians and others grieved, they were also asking a key question: Was the crash an accident—or swift blowback from ISIS, which claimed responsibility for the attack and called it vengeance for President Vladimir Putin's bombing in Syria?

Even as evidence mounted that a bomb was to blame—from satellite data showing a flash of heat just before the plane went down to photographs apparently showing the fuselage blasted outward by flying shrapnel—Russian officials rushed to deny extremists' involvement.

"There is no connection between the Russian bombing operation in Syria and the Metrojet Flight 9268 crash," Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov assured Russian TV viewers three days after the incident. Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi took the same line, saying, "Any propaganda reports that the jet was somehow downed by terrorists are aimed at destabilizing the region and tarnishing Egypt's image." And when the U.K. suspended all passenger flights to Sharm el-Sheikh and organized special flights to repatriate 20,000 Britons—with their luggage flown on a separate cargo plane because security experts deemed it too vulnerable to sabotage—Russian officials initially slammed the flight ban as political.

"There is geopolitically motivated opposition to Russia's actions in Syria," warned Konstantin Kosachev, chairman of the International Affairs Committee of the upper house of Russia's parliament, slamming those who would want to blame the disaster on a jihadi response to Russia without proper evidence. Nonetheless, a full week after the tragedy, Putin accepted the advice of Federal Security Service head Alexander Bortnikov and belatedly suspended all flights from Russia to Egypt until the cause of the crash becomes clear. Finally, when Egyptian authorities confirmed on November 9 that they were "90 percent certain" that a bomb brought down the plane, Dmitry Kiselev of the state-controlled Rossiya-1 anchored a news program devoted to the theory that the U.S. had cut a deal with ISIS to turn a blind eye to attacks on Russian planes in exchange for leaving American and British planes alone. Kiselev quoted U.S. Defense Secretary Ash Carter warning Russia that its campaign in Syria would lead to extremist attacks—"Were Carter's remarks merely bad taste?" asked Kiselev, a Kremlin loyalist who also heads Russia's main news agency. "Or did he know something in advance?"

Until the crash of Flight 9268, Russia's monthlong bombing campaign in Syria had nothing but upside for the Kremlin. At home, Putin's approval ratings have risen to unheard-of heights, topping 88 percent in one October poll, even as Russian exports dropped 31.9 percent in January through September, imports dropped 38.8 percent, and Central Bank reserves dropped $160 billion to a riskily slim $350.5 billion. Internationally, Putin took the opportunity to present Russia as an indispensable power in Syria, stepping where the West has, for the most part, feared to tread.

Now the Metrojet tragedy looks like the first installment of a substantial bill the country might have to pay for Russia's first intervention in a Middle Eastern conflict since the fall of the Soviet Union. A poll published on the eve of the crash by the independent Levada Center showed that a slim majority of Russians—54 percent—supported the air campaign in Syria, though a decisive 66 percent opposed putting Russian troops on the ground in the conflict zone.

In a Western democracy, an attack of this magnitude might lead to a crisis of confidence in the country's leadership. Not so in Russia. In the wake of the decision to suspend flights, Russia's social media filled with pictures of some of the 45,000 Russians stranded in Egypt's Red Sea resorts, showing up at Sharm-el-Sheikh Airport sporting Putin T-shirts. Over the year and a half since Russia's annexation of the Crimea, Kremlin-controlled TV channels have "told the people that the world is hostile and that their leader is defending Russians against an amazing mix of enemies, from American imperialists to Islamic terrorists," says one Moscow-based TV news producer at a state-controlled channel, who requested anonymity when criticizing the Kremlin. "The more enemies around, the more people feel the need to be protected. This formula is as old as politics."

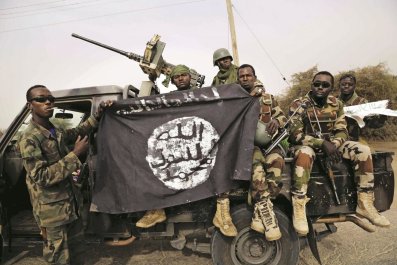

Already, loyal media outlets have cast Russia's campaign in Syria as a historical struggle between civilization and barbarism. "We have saved Europe for a fourth time," boasted Kiselev earlier this month. "First the Mongols, then Napoleon, Hitler—and now we have saved them from ISIS."

Going on past form, Putin is a leader who thrives on the politics of fear. He has been through trial by extremism before—many times—and each time he has answered violence with violence.

Putin's reputation as a tough, no-nonsense man of action was born in the aftermath of attacks in 1999, when a series of still-unexplained bombings of apartment buildings in Moscow killed over 300 people. Putin, then prime minister, ordered an invasion of the rebel republic of Chechnya, which propelled him to the presidency the following year. His first years in power were marked by repeated bombings and other militant attacks. Each one strengthened rather than weakened the new president.

In 2002, Chechen militants seized a theater in suburban Moscow in a siege that left 170 people dead—including 133 hostages, all but two of whom died from sleeping gas used to subdue the attackers. In 2004—the bloodiest year of Putin's reign so far—female Chechen suicide bombers killed 51 people in twin attacks on the Moscow metro system. Another pair of Chechen female students from Grozny bribed their way onto two Russian domestic flights from Moscow's Domodedovo Airport in August 2004 with luggage packed with explosives, killing 89 people. And on September 1 of that terrible year, a suicide squad of Chechen fighters took more than 1,100 people hostage in a school in the Russian town of Beslan. By the end of the militants' battle with Russian security forces, 335 people were dead, many of them children.

Putin's famous response to those first attacks became a trademark of Putin's KGB-trained toughness that bordered on thuggery: "We will rub them out in the shithouse if necessary," he said. But ordinary Russians were reassured. Ramzan Kadyrov, the leader Putin installed in Chechnya, did indeed bring peace to the troubled region through what human rights groups have described as the wholesale application of state terror, which shocked Russian liberals but put an end to the attacks.

Putin's annexation in 2014 of Ukraine's Crimean Peninsula (considered by most of the world to be legally part of Ukraine), his support for rebels in eastern Ukraine and now his bold deployment of Russian aircraft in Syria suggest that Putin's worldview remains the same: that violence can solve Russia's geopolitical problems and boost his own popularity at home. "We will be fighting terrorism in Syria or anywhere," Putin told state television three days after the Metrojet crash. "No one will ever be able to terrify the Russian people."

The problem is that if ISIS is discovered to be responsible for the Metrojet disaster, Putin's most natural reaction will be to ramp up his Syrian campaign in retaliation. And the Kremlin's arm's-length, video-game-like, remote control air campaign risks escalating into a dangerous quagmire of asymmetric war against a foe more numerous, ruthless and murderously inventive than even the Chechens.