It is early afternoon on a gray Saturday in Seattle, and David Burd has just checked into his spacious dressing room in the Seattle Center, hours before the scrawny Jewish rapper, who calls himself Lil Dicky, is to perform his biggest show yet, at the Bumbershoot music festival. "This is probably the biggest dressing room I've ever had," Burd says, as he scans the festival's poster for his name. "Where am I on this thing?"

Burd's hype man, GaTa, stretches out on the couch and says, "I need some bitches, man. There's some fine-ass girls in Seattle. Fine-ass Asians out here too. Fine-ass black girls, everything. I like Seattle."

"I like Seattle too," Burd agrees. But he's not concerned with "bitches" at the moment. "We've got to get product," he says, with a sense of urgency. I ask if he means weed. "No," Burd replies. "Body wash, shampoo."

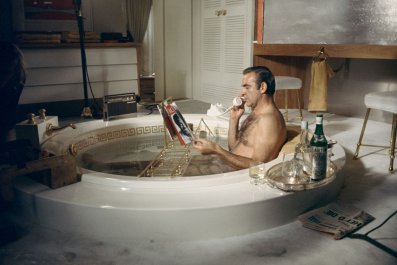

A few minutes earlier, Burd had discovered the dressing room's most critical feature: showers—a "game-changer" because they mean Burd won't have to schlep back to the hotel after his set. "I get incredibly sweaty and feel terrible," he says. "I don't think I've gone more than 24 hours without showering at some point in the last five years."

Lil Dicky surprised the hip-hop world in August when his debut album, Professional Rapper, hit the top of Billboard's rap chart, thanks in no small part to a duet with Snoop Dogg on the title track and the resulting video, which racked up more than 8 million YouTube views. As the curly-haired advertising copywriter-turned-rapper from the upper-middle-class Philadelphia suburb of Cheltenham prepared to take the main stage at Bumbershoot, he's more focused on getting clean than he is getting laid.

"Do you think they sell any soaps around here?" Burd asks his manager, Mike Hertz.

Hertz glares at him. "Do you hear yourself right now?"

"I want to go somewhere that has product," Burd says. "That's all I'm saying."

"OK, OK," Hertz says. "I'll look for a CVS for you."

I'm trying to imagine what the conversation in the next dressing room over is like. I doubt it's about shampoo and body wash, but this is a big part of Lil Dicky's appeal: He has yet to shed the neurotic facets of his personality just because he's suddenly a popular musician. He raps about Adderall and soda water, not weed and Alizé. He calls this his "Looking for Love" tour, because he genuinely hopes he's going to meet his wife-to-be on the road.

He's not afraid to admit he finds having sex with a woman for the first time terrifying and that he considers himself clumsy in the sack. ("I'm getting better, though.") Sometimes onstage he can't keep rapping because he starts dry-heaving in the middle of a verse. His rider has the cinnamon-flavored liqueur Fireball on it, and face wipes. He wants to add Pop-Tarts and "a lot of Perrier." He's a "Professional Rapper" who still doesn't act like one.

GaTa finds all this disturbing, and they are constantly arguing about it. "You should take advantage; live a little," GaTa advises Burd. "As far as being a rapper, some of the shit that comes towards you—hos, sluts. You can't be picky with this type of shit."

Burd demurs. He's spent the last half-hour or so explaining that yes, as a rapper, he has opportunities to sleep with women he didn't have before. But as a rapper at only a certain level of fame, these are not the opportunities he's looking for. "I don't view the opportunities I have as really prime opportunities," he says. "Sure, I could probably end up having sex with—I don't mean to sound chauvinistic, but—like, a 6 or a 7. One time a girl came up to me and said, 'I had so much fun at your concert, you seem like an awesome guy. I'd love to get a drink with you afterwards.'"

Another time, two girls offered to perform sexual acts for him. "They were disgusting, but I still wouldn't have done it if they were hot, because what kind of STDs does a girl like that have, offering up head to a rapper?"

Sexually transmitted diseases are another frequent topic of conversation in Lil Dicky's world. "I'm very, very, very concerned with STDs," he says. "And I find sex to be a pretty stressful, overwhelming ordeal just to begin with." Not all sex, mind you, but it's the first time—the "tone-setting sex," he calls it—that's stressful. Before he started rapping, he'd had sex with only five girls. Now, he says, he's up to 19. "I'm not going to start having sex with more girls than I would otherwise," he says, as GaTa shakes his head in disappointment.

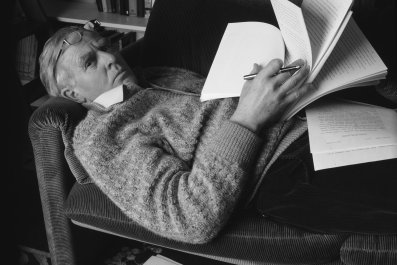

If Burd seems a little uncomfortable enjoying the spoils of a baller life, it's because he has in many ways stumbled into a rap career. After growing up in Cheltenham, he went to the University of Richmond, then landed a job at the advertising agency Goodby Silverstein & Partners in San Francisco. He delivered a monthly progress report as a rap video; his bosses loved it and offered him a job in the creative department. In his spare time and on his own dime, Burd started making rap music. His first single, "Ex-boyfriend," depicts his jealousy and insecurity at learning that his girlfriend used to date a handsome, seemingly perfect guy. The video hit 1 million views in its first 24 hours.

In 2013, he released the debut mixtape So Hard and self-funded 32 songs and 15 music videos that he released once a week for five months, before turning to Kickstarter to raise $70,000 for his next round of songs, videos and tours. That November, the campaign raised $113,000, and Lil Dicky held his first concert in Philadelphia the following February.

His songs depict rap battles with Hitler and getting roughed up by black guys on a trip to East Oakland, California, because he (jokingly) sought to change the rap landscape's "hypermasculinity and irrational swagger." He's gifted, both musically and lyrically, but he's an unlikely star—and he knows it. His swag is self-deprecating, and his bravado is a joke. He's the Jerry Seinfeld of hip-hop, and his shtick is resonating with plenty of (white, young, male) fans.

This presents Burd with a golden—though precarious—opportunity. In an interview published by the Vice music site Noisey this past October, Burd found himself on the defensive after Features Editor Drew Millard suggested he was "almost gleeful about being a white male," and Burd wound up making a few unfortunate comments he's since had to try to walk back in order to convince the world he's a satirist, not a racist. "By putting this music out, I think I genuinely eliminated 80 percent of the previous jobs I was qualified for," he told Noisey. Millard's takeaway: "At his best, Lil Dicky crosses Big Sean's goofy wordplay with Larry David's satirical eye, or a one-man Lonely Island with better flow. At his worst, he is a defensive, clueless asshole."

At Djbooth.com, Lucas Garrison (who is white) took issue with what he considers Burd's attempt to "have his cake and eat it too." He lampoons his white privilege but also seems to be genuinely complaining about how disadvantaged he is by trying to be a white rapper in a black genre. If he looked like Rick Ross, Burd once blogged, he'd be able to say what he wants—the N-word, he offers, for example. Asked Garrison, "Where does the joke end and the serious rapper begin?"

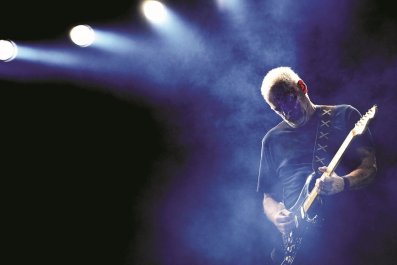

Back in Seattle, Burd peers through a fence that separates him from a throng of mostly white, young, male fans who've muscled their way to the front of the main stage. As the scheduled time for his set ticks closer, they start shouting, "We want Dick! We want Dick!"

Burd loves it. This is the biggest crowd he's ever performed for, and, as self-deprecating as he often is, he also has big ambitions. "Deep down, I want to be a big rapper," he told me the first time I talked to him, in a phone interview in July. "I want people to love what I'm doing. Does Drake know who I am? Does Drake care?"

Does Lil Dicky need to enroll in a racial- and gender-sensitivity class in order to reach the level of fame to which he aspires? Probably not. Burd argues that people just need get past the shock and they'll be fine. "People see a South Park episode and there's racially insensitive jokes—nobody bats an eye because they're expecting that, in that context. In hip-hop, they don't expect that kind of thing because it's a white person in a predominantly black world." Burd's humor, he insists, is an homage to hip-hop because "the way you respect hip-hop is by being true to yourself."

At Bumbershoot, he unbuttons his Seattle Mariners jersey and charges out onto the stage, rattling through 11 songs at breakneck speed. For his final number, "Lemme Freak," Hertz gets the flowers ready and Burd points to a young girl in the front row, inviting her to come up onstage, where he has her sit in a chair. Halfway into the number, Burd climbs into her lap and "freaks" the girl wildly. (She seems delighted, if shocked.) A few seconds later, he rips off his sweat-shorts and does it again, this time in his underwear. For a guy who considers himself sexually clumsy, Lil Dicky sure moves like a professional rapper onstage.

After the show, the girl trails him backstage and insists on a picture. Burd poses holding two fingers about an inch apart, implying he's not that well-endowed. It's his lil trademark.