Updated | With every beer in the West Berlin pub, Jeffrey Carney grew more morose. The U.S. Air Force intelligence specialist, only 19, was struggling with his parents' divorce, fighting with his bosses and, worst of all for someone with above-top-secret security clearances, coping with a clandestine gay sex life. But Carney had another secret that had nothing to do with his personal life: From his perch as a linguist eavesdropping on Soviet-backed forces in Eastern Europe, he knew that Washington's portrayal of the other side was a lie. The enemy wasn't an unstoppable juggernaut preparing to invade the West. Its combat units were barely functional. And it was the U.S. that was trying to provoke the Soviets into an incident that could lead to war.

Depressed and looking for an escape, Carney bolted for Checkpoint Charlie, the gateway to Communist East Berlin, near midnight on April 22, 1983, and asked for political asylum. It didn't work out as planned; within hours, East German intelligence agents blackmailed him into returning to his unit as their spy. If he refused, they made clear, they'd leak his planned "defection" to his bosses.

Carney's name has largely been forgotten in the annals of Cold War espionage. Compared with the big-time moles flushed out in the 1980s, like the CIA traitor Aldrich Ames, Carney was a worm. News of his capture and conviction in 1991, two years after the Berlin Wall fell, seemed like a footnote to an era best forgotten amid the giddy celebrations of East-West reconciliation.

But a newly declassified, top-secret U.S. intelligence study, released on October 24, suggests that Carney's concerns were well-founded. Called "The Soviet War Scare," the 109-page document was obtained only after years of litigation by the National Security Archive, a private research group based at George Washington University. The study analyzed the unanticipated effects of a massive NATO war game, code-named Able Archer 83. It found that "Soviet military leaders may have been seriously concerned that the U.S. would use Able Archer 83 as a cover for launching a real attack," and that "the war scare was real, at least in the minds of some Soviet leaders."

"[W]e may have inadvertently placed our relations with the Soviet Union on a hair trigger," says the 1990 study, prepared for the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, a group of top former government and industry leaders. "This situation could have been extremely dangerous if during the exercise—perhaps through a series of ill-timed coincidences or because of faulty intelligence—the Soviets had misperceived U.S. actions as preparations for a real attack."

That was exactly what worried Carney—that one shot would lead to another, and maybe even a nuclear war. "We underestimated the Russian psyche," Carney says. "They were institutionally paranoid. The average American would not launch a rocket and shoot a plane out of the air. But they don't think like we do."

Every traitor, of course, has a dozen rationalizations for his treason. And Carney's was that he believed he could talk the Communists down and avert a world war. "If you're helping the paranoid schizophrenic not respond paranoid-schizophrenic style, then you've done a good thing," he says. "Because if they shoot down a plane, then we go back and hit something, and then they respond and hit something. We've seen it a million times in history."

As Able Archer unfolded in the summer of 1983, Soviet state-controlled radio started making announcements "several times a day" suggesting a U.S. attack was imminent, the study notes. New street signs went up in Moscow and other cities showing the locations of air raid shelters. A Soviet air force unit in Poland began carrying out drills to speed up the transfer of nuclear weapons from storage to aircraft. Some in the Ronald Reagan administration worried that the Soviets were preparing for an invasion of Europe. In response to a Western attack, Moscow's war doctrine called for the destruction of most European cities and ports using nuclear weapons, followed by a massive ground invasion that would put Soviet troops on the Atlantic in 14 days.

"One misstep," Reagan recalled years later, "could trigger a great war."

A Cold War Taboo

Carney had no idea what he was getting into when he crossed into East Berlin in the spring of 1983. His access to some of the Pentagon's most sensitive electronic-spying operations had driven him to reconsider his initial enthusiasm for the election of Reagan, who had dubbed the Soviet Union "an evil empire" bent on crushing the West. Newspaper reports at the time described the Russians as unstoppable. "Perhaps the first moment I realized there was a problem, a big discrepancy, was while I was waiting for the bus to go to work one day," Carney recalls. "Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper, had an article about Soviet superiority in the European theater. I remember laughing with a friend, a Russian linguist, about the numbers and technical information cited in the report. It stood at complete odds with what we saw in our intel reports every day."

The truth, he says, was that Communist-allied units were hampered by fuel and food shortages, alcoholism and even cholera, picked up by soldiers rotating into East Germany from the Soviet Far East. Soldiers were siphoning off brake fluid to get high. He doubted many were battle-ready. "Ronald Reagan," Carney began to think, "was intent on making Russia an evil empire, whether it was evil enough on its own or not."

At work, he began openly espousing his sympathies for the Soviet-backed Sandinista government in Nicaragua. He loudly complained that the U.S. was encouraging anti-Soviet Poles to hijack aircraft and fly them to Berlin. He requested a transfer out of intelligence but was turned down.

Keeping his homosexuality under wraps, meanwhile, was excruciating. "An airman or soldier being drummed out for being gay was no rarity back then," he says. "I shared the fear that I, too, would be discovered, shamed and thrown out of the only thing that had given my life structure." So he "took off" and fell into the gleeful embrace of East German intelligence, the notorious Stasi, which claimed him from the border guards at Checkpoint Charlie. Its veteran spy handlers quickly dismissed his illusions of settling peacefully in the East. They told him they were sending him back to his unit as their mole. And if he refused? They had his military ID and photos of him in their presence—plenty of blackmail material.

"So I went back a very unwilling spy, thinking I could get myself out of this quickly," he says. "But, you know, it doesn't work that way. It's like the Mafia—you don't get out."

'People Are Going to Be Shot Down'

Beginning in May 1983, Carney started looking for "important" documents to steal. The more he read, the more he was concerned about Washington's electronic warfare programs and weapons, which could fry the Soviets' command-and-control telecommunications. "[They] were mind-boggling in their reach and ability," he says. "Many of them were purely offensive, and...would have only found use in a first-strike scenario."

Later that year, Carney learned that U.S. warplanes were about to fly into Soviet airspace to simulate an attack on a sensitive military site and measure how the enemy responded. War jitters were already high with the impending deployment of U.S. Pershing ballistic missiles in West Germany. In September, the Russians shot down a Korean airliner that wandered over its missile testing area on the Kamchatka Peninsula, in the Soviet Far East. Fearing a similar result, Carney rushed to tell his Stasi East German handler what was coming.

He says another incident in particular, in the fall of 1983, drove him from an "unwilling to a very willing spy." Since it's still classified, he refuses to divulge it further, for fear it could land him back in prison. "It was an intentional, aggressive provocation of the Soviet Union in a very sensitive area," he says, "that would have made [Russian radar monitors] flip out."

He adds, "When it was explained to me, I said, 'You've got to be kidding. You are going to push their buttons. People are going to be shot down.'"

That fall, Russia and the United States nearly stumbled into a nuclear exchange. On the night of September 26, 1983, alarms went off inside a Soviet radar station 90 miles southwest of Moscow, indicating that an American Minuteman intercontinental nuclear missile was incoming. Then the klaxon went off, signaling another was en route, then another and then another—five in total. The unit had only minutes to verify the attack. Panicky air defense operators were screaming that it was real. Moscow had to unleash a counterstrike, they said, or lose its missile forces.

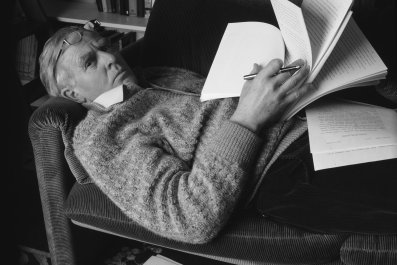

Only the cool patience of the Soviet unit commander, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, prevented a full nuclear exchange, according to an account by Washington Post reporter David Hoffman in his 1999 book, The Dead Hand. Petrov decided that the data, relayed by a Soviet satellite, combined with the absence of any other incoming missiles, was false. He told Moscow to stand down. "I had a funny feeling in my gut," Petrov told Hoffman. "I didn't want to make a mistake. I made a decision, and that was it." But as he told the BBC in 2013, "They were lucky it was me on shift that night."

11 Years, Seven Months and 20 Days

In 1985, with U.S. investigators unearthing Soviet spies by the handfuls, Carney fled to Mexico City from a duty post in Texas and asked for protection at the East German Embassy. This time they took him in, flying him to East Berlin via Havana and Prague. But the Stasi wasn't done with him yet. For the next four years, it put him to work eavesdropping on U.S. commanders in West Germany as well as the U.S. Embassy in East Berlin.

Then, in 1989, the Berlin Wall crumbled and the Stasi dissolved. Carney found work as a subway driver, but in 1991 an Air Force security team, tipped off by ex-Stasi informers, swept him off the street in the former East Berlin and bundled him off to Templehof Airport for an "intense" interrogation in which he was denied legal counsel. Twenty-eight hours later, he was secretly put aboard a U.S. military plane and flown through the night to Washington.

He soon got his day in court, pleading guilty to espionage and desertion, for which he received a 38-year sentence. In 2002, after serving 11 years, seven months and 20 days, he was released from the stockade at Fort Leavenworth.

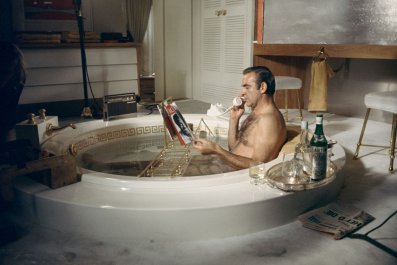

Now puffy-faced and thick at the waist, Carney says he cannot get a job because of his conviction. For income, he collects rents from a building he partly owns in Ohio. In 2013, he self-published a memoir, Against All Enemies: An American's Cold War Journey, which drew scant attention. But now that the U.S. has released the top-secret report, Carney says the document explains why he helped the Communists. Spies like him, on both sides, helped keep the peace, he argues, by ferreting out each side's true military capabilities and intentions. That's self-serving, since the disclosures of just two of the Soviets' moles, Ames in the CIA and Robert Hanssen in the FBI, led the Kremlin to kill perhaps several dozen U.S. spies in Russia.

But Carney has few regrets. "I regret the pain I caused people, I regret the fact that I was in a position where I didn't have the whole picture and I made decisions where I ended up hurting people," he says. "Unintentionally, though, I think what I did—and there are hundreds and hundreds of people who did what I did, on both sides: American spies, Russian spies, German spies—all of us together made it basically impossible for a war to break out. And I think that's where the focus should be."

Correction: A caption in this article originally incorrectly stated that Carney tried to defect to the USSR. Carney tried to defect to East Germany. A previous version of this story also implied that the Stasi dissolved and then the Berlin Wall crumbled. It was the other way around. The story has been adjusted for clarity.