I was fortunate enough to be invited by the watchmaker Omega to attend the premiere at the Royal Albert Hall of Spectre, the latest James Bond movie. While waiting for the lights to dim, I flicked through the souvenir program and noticed a full-page advertisement that read: "We Turn Brands Into Screen Icons." This alchemy is offered by the advertising company, Digital Cinema Media. I am sure that DCM does a grand job—but when it comes to propelling luxury goods into cinematic immortality, to quote Carly Simon's theme tune from The Spy Who Loved Me, "Nobody Does It Better" than Bond.

All dramatic genres have their conventions: Take the classical unities of time, place and action that characterize the drama of the ancient world, for example, or the gory conclusion of the classic revenge tragedy. The Bond movie, with its glorious festival of branded consumption, is no exception.

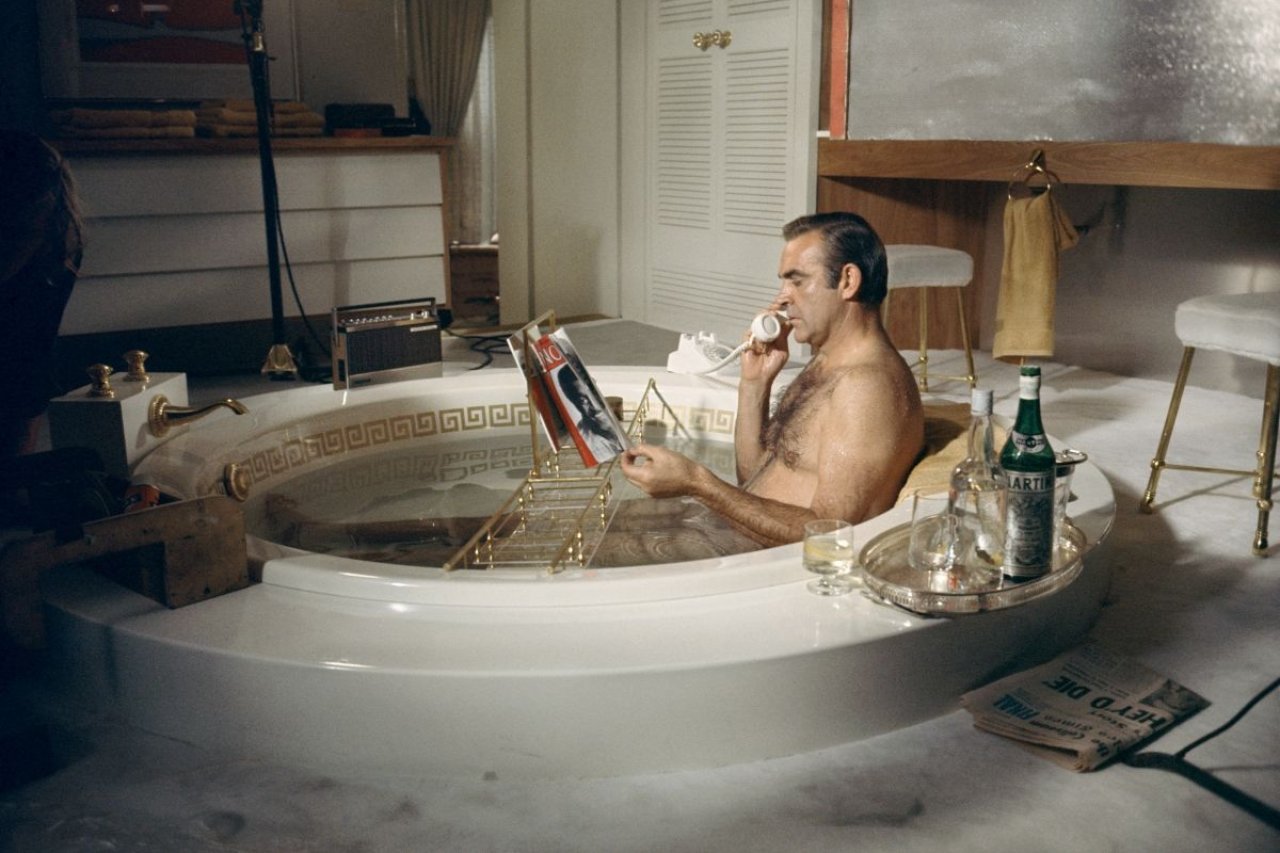

Any 007 outing is required, as if by law, to feature an invigorating pre-title action sequence; a megalomaniac (preferably with a slightly foreign accent) bent on large-scale destruction; at least one conurbation-sized explosion; gadgets galore; and levels of sex and violence that would be familiar to students of Jacobean drama. But most important of all is the stuffthe products, the lifestyle accoutrements, without which Bond would not be Bond. Take away the dinner jacket, the Aston Martin, the Beretta, the vodka martini and you have just another action hero. And that makes the Bond franchise an unusually welcoming home for contemporary, as well as classic, brands.

Related: What Makes a Great James Bond Villain?

Over the years, product placement has become a convention as fundamental as gunplay to the familiar and satisfying progression of Her Majesty's least secret agent through the carefully choreographed car chases, detours to exotic locations, and scenes of hand-to-hand combat and seduction. With Spectre you are in for a treat if you like Omega watches, Aston Martin cars, Range Rovers, Bollinger champagne, Tom Ford suits and sunglasses (especially the pair Bond wears in Austria), Crockett & Jones shoes, Sony telephones, Belvedere vodka, Brunello Cucinelli leather jackets, N.Peal pullovers, Sunspel boxer shorts, Globe-Trotter suitcases, andwe're nearly finishedGillette razors. The official Bond razor is the Gillette FlexBall (although I think Gillette Thunderball has a better ring to it).

I must admit to having missed the shaving sequence in Spectre, but happily I was aware of 007's facial hair removal preferences thanks to heavy pre-film advertising, in itself a tradition that stretches back over 50 years to the first Bond film, when Smirnoff placed an advertisement before the release of Dr. No. This ad was so far in advance of the public's understanding of what a Bond movie was that it needed to explain that Sean Connery was an actor and that he had been chosen to portray Bond because "he fitted the part to perfection."

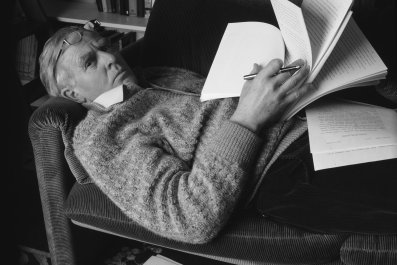

Even before the film franchise had established itself the idea of James Bond as a sort of walking, talking, killing catalogue model was well-established by the original Ian Fleming novels. This latest two-and-half-hour lush serving suggestion of the life deluxe is wonderfully faithful to Fleming's vision of the world. Kingsley Amis, who wrote a Bond novel pseudonymously as Robert Markham, identified it as the "Fleming effect," a sense of plausibility that props up even most far-fetched of yarns. The Fleming effect is founded on the British spy novelist's mastery of the material world. Anthony Burgess put it rather well when he said, "It is the mastery of things rather than people that gives Fleming his particular niche."

Related: Fleming Is Forever: Why You Should Read the James Bond Books

Fleming was a brand fanatic. He could not help himself—even everyday appliances were namechecked. "Ventaxia" [sic], the electric fan manufacturer, is the first brand to be noted in line five of Chapter 1 of Moonraker. But it was as a student of the good life that Fleming excelled: his novels are full of vintage wine and special blends of cigarettes in lavishly described cigarette cases.

Curiously, although much is made these days of Bond's wardrobe, Fleming was vague about the clothes his hero wore. He writes more about the cut and cloth of 007's clothes than the labels. (In those days Bond was bespoke tailored rather than a prêt-à-porter man.) By contrast, just as William Blake described John Milton as being "of the Devil's party without knowing it," so Fleming dresses his villains far more carefully than he does Bond. Moonraker's Sir Hugo Drax wears "a dark blue pinstripe in lightweight flannel, double-breasted with turnback cuffs, a heavy white silk shirt with a stiff collar, an unobtrusive tie with a small grey and white check, modest cufflinks which looked like Cartier, and a plain gold Patek Philippe watch with a black leather strap." And my personal favorite is Count Lippe, a supporting villain from Thunderball, who dresses in "a casually well-cut beige herring-bone tweed that suggests Anderson and Sheppard. He wore a white silk shirt and a dark red polka-dot tie and the soft dark brown V-necked sweater looked like vicuna." Lippe also favors shirts by Charvet and drives a violet Bentley.

Anyone who can begin a novel with the line, "There are moments of great luxury in the life of a secret agent"—as Fleming does in Live and Let Die—clearly enjoys the better things that life has to offer and this juxtaposition of evil and aestheticism conveys a message that is as relevant today as it was when Fleming started writing his novels in 1953. There is a reassurance about the fact that although the world will always be threatened by violent maniacs, there is also always the consoling presence of a beautiful watch, fast car, exquisite suit (or if you prefer Gillette FlexBall).

At one point in Spectre, Bond utters the words "tempus fugit"—director Sam Mendes is after all an Oxford and Cambridge man—as coded instructions to his girlfriend to throw an exploding Omega watch at the long-suffering villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld, played by Christoph Waltz. Leaving the Albert Hall after the screening another Latin tag sprung to mind: "Carpe diem." To quote a line from the 1964 amorality tale, Nothing But the Best, starring Alan Bates: "Let's face it. It's a rotten, stinking world. But there are some smashing things in it."