The cops will be coming for me any moment now. For the past hour, I have been acting suspiciously, driving through the pavement maze that is Oakland International Airport, pausing in empty lots, lingering on empty stretches of road. I don't think it's illegal for me to be here, but it's probably not quite kosher either.

I'm just trying to find a place to watch planes take off and land. If I were still in New York, I'd head to Rockaway Beach, from where you have a perfect view of jumbo jets creeping toward John F. Kennedy International Airport. But I am new to Northern California, and my trip to Oakland International has proved acutely inauspicious. The best I can do is a parking lot from where I watch several jets—Southwest, judging by the garish fuselage—crawl into the afternoon haze, impelled ever higher by some vast cosmic force.

I might console myself by heading to the Oakland Aviation Museum, which I had seen from one of the roads surrounding the airport. But the museum is closed and, really, does not appear to be much of a museum at all. Tucked between rental car lots and enclosed by barbed-wire fence, it seems to also function as an aviation junkyard. There is, however, a 1946 Solent III flying boat in an outdoor courtyard. Apparently, it was a prop in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Its steps are down, beckoning with stiff cocktails and slim stewardesses who smile beatifically as they hand you a dinner menu. Will it be the dover sole, sir, or the filet mignon? But the door to the airplane is closed, and the fantasy quickly vanishes. Such is flight today: We dream of martinis while sipping lukewarm Bud Lights.

Less Than Angels

I used to despise flying. I won't bore you with the details, because the fear isn't an original one. Let's just say this: I once took a train from San Francisco to New York. I want to pretend the journey was worth it, but anyone who has traversed rural Illinois will know better.

What truly bothered me, though, was how many other people readily confessed to the same fear. People I respected, people free of pervasive neurosis, would admit to anxiety attacks upon takeoff, fatal thoughts upon the first sign of turbulence. They, too, took trains. And then there are the celebrities: Jennifer Aniston, Ben Affleck, Whoopi Goldberg. Colin Farrell is afraid of flying, and he doesn't look like he's afraid of anything.

But much like Ms. Aniston and Mr. Farrell, I routinely need to fly. And so I had to get over that fear, and I had to do it in a way that didn't involve four shots of Maker's, each one chasing a Klonopin. Snooping around the Internet is usually disastrous for the fearful, but the fear-of-flying community is relatively responsible in comparison to the does-this-mole-look-weird? community. Reading various websites devoted to the safety of flight, I eventually found my way to Ask the Pilot, an online column by Patrick Smith, who has been flying for airlines for 25 years. I don't want to say Smith entirely cured my fear of flight; I was already on my way by the time Cockpit Confidential, a collection of his writings, came out in 2013. The book did something more rare: It made me enjoy, not just tolerate, the early-morning flight from New York to Minneapolis. With a connection in Miami.

Smith explains everything about flight, and he does it in such a charming way that you don't realize just how heavily you're geeking out on the mysteries of the code-sharing agreement. Smith can explain why, as an Airbus plane is taxiing, it makes that weird dentist-drill sound; why lightning isn't really a danger during flight; and what happens when you flush the toilet. Best of all, Cockpit Confidential is a reminder that flight remains an act of human supremacy over natural forces, gravity foremost among them. "We've come to view flying as yet another impressive but ultimately uninspiring technological realm," he writes. And, a little later: "Aren't we forfeiting something important when we sneer indifferently at the sight of an airplane—the sheer impressiveness of being able to throw down a few hundred dollars and travel halfway around the world at nearly the speed of sound?"

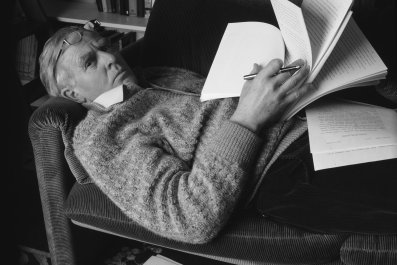

The essential wonder of aviation is also the subject of Skyfaring, by the pilot Mark Vanhoenacker. Much like Smith, Vanhoenacker wants us to remember that flight is about more than just earning points and fighting for legroom. That while your flight may have been dreary, flight itself is anything but. The premise of Skyfaring is alluring, and Vanhoenacker obviously loves his job, yet his book is overloaded with poetry, so verbose that it never quite achieves the necessary lift. His prose is at once turgid and formless. The innate poetry of flight is hard to match in prose, and few have done it well. In that small group is the writer Saul Bellow, describing takeoff in this passage:

New York leaned gigantically seaward, and the plane with a jolt of retracted wheels turned toward the river. The Hudson green within green, and rough with tide and wind. Isaac released the breath he had been holding, but sat belted tight. Above the marvelous bridges, over clouds, sailing in atmosphere, you know better than ever that you are no angel.

Bellow captures the central paradox of flight: We know we are no angels, but isn't there something more than human about puncturing the clouds?

A Unique Majesty

On September 17, 1908, Orville Wright was at Fort Myer, in Virginia, showing off one of the Flyers he had built with his brother Wilbur. On board with him was U.S. Army Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge. The historian David McCullough describes the scene in his latest book, The Wright Brothers, about the two bicycle shop owners from Dayton, Ohio, who pioneered aviation. Wright and Selfridge made three circles at an altitude of 125 feet, but on the fourth attempt something went wrong. On the ground, an observer uttered words no aviator wants to hear: "That's a piece of the propeller." Wright shut off the engine, but "the machine turned down in front and started straight for the ground," as Orville would write to his brother.

Both men were taken to the hospital with serious injuries; Selfridge succumbed to his, thus earning the distinction of being the first casualty of powered aircraft. He had flown that day instead of another prospective passenger eager to test the Wrights' new machine: Theodore Roosevelt. Made aware of the request, Orville had demurred, confessing to the press, "I don't believe the president of the United States should take such chances."

This nation's first great airline was Pan American World Airways, founded in 1927 by Juan T. Trippe. While based in Key West, Florida, he managed to secure lucrative routes to Cuba, then the Americas; within a few years, Pan Am ruled the Pacific too, its "China Clipper" flying boat becoming the first craft to cross that ocean in 1935. There are nearly 100 books about Pan Am, according to a site dedicated to the airline, from The Fall of Pan Am 103, about the bomb that brought down a Pan Am flight over Lockerbie, Scotland, to Timmy Rides the China Clipper, a kids' book whose cover shows the famed flying boat banking over a tropical island. Today, the only relic of the airline in New York that I can think of is a service road—Pan Am Avenue—tucked into the side of JFK Airport in Queens. I do not recommend a visit.

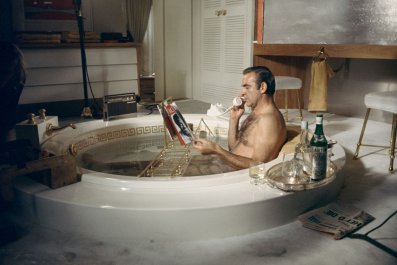

The glories of the postwar Jet Age can be relived in Airline Visual Identity: 1945-1975, perhaps the most handsome book published in the Western world in the past two years. This resplendent compendium of airline posters costs nearly as much as a cross-country flight ($400), but it is worth it for anyone who wants to be reminded of a time when flying was sexy, dangerous and prestigious. Long before it became common to board a flight in sweatpants, the world was a mystery, and the airplane was a means of revelation. If you ever need to get Don Draper a gift, this should be it.

Pan Am is gone, but its crucial partner from the glory days—Boeing—remains. In many ways, the success of the Boeing passenger jet is responsible for air travel as it is today: extremely safe, relatively inexpensive and deeply unpleasant. No single craft embodies the Boeing way like its workhorse 747, which first took to the air in 1970 at Pan Am's behest. It hasn't come down to earth since. "The 747 has a unique majesty," writes the airplane's lead designer, Joe Sutter in 747. "Passengers love it, and so do pilots, but it's what this airplane has done for humanity that's significant. Since the first 747 entered service in 1970, the world 747 fleet has transported more than 3.5 billion passengers" a distance that is "the equivalent of 75,000 trips to the moon and back."

The implication of this boast is obvious: Sutter engineered a machine that promises to take you anywhere and get you there alive, maybe even with your battered suitcase in tow. If someone told me that Boeing had a better safety record than the common sparrow, I would not be surprised. But total safety is an illusion, and even those of us who fear flying need to be reminded of that. Of the recent slew of books about aviation, only one, Flight 232 by Laurence Gonzales, is about a crash—that of United 232, which came down near Sioux City, Iowa, on July 19, 1989. The spectacular crash landing, which was captured on video, killed 111 as the jet tumbled like a toy tossed by a surly child. But, remarkably, 185 people survived, a testament to the skill and sangfroid of the flight crew.

United 232 is also one of several accidents featured in Charlie Victor Romeo, an exceedingly unsettling 2013 film (adapted from a play) in which a flight crew acts out cockpit scenes from several doomed craft. There are few props and no pyrotechnics of the James Cameron variety, just dumpy pilots in bad pilot outfits, sitting at antiquated flight controls. This is, of course, intentional. The film derives its power from an adherence to transcripts of cockpit voice recorders (CVRs: hence the film's name, rendered in military alphabet), with your imagination doing most of the work. At the commencement of each scene, you know that dread looms, that the only reason we remember Japan Airlines Flight 123 is because it was a catastrophe.

In the century since Orville Wright and Thomas Selfridge fell from the sky, humanity has toiled with impressive focus to make flying the safest mode of transport. We needed to justify our hubris, to prove to ourselves, and maybe to the gods, that our conquest of the sky was no foolish pursuit. We have largely succeeded, but once in a while, those gods take their toll.

My Top Gun Fantasy

One afternoon several months ago, I went to JFK Airport without intending to fly. The occasion was a party at Terminal 5, the home of hip, low-cost carrier JetBlue. The occasion was the opening of an outdoor green space in the terminal, the only one of its kind in the New York metropolitan area.

JFK is, today, no one's idea of a glamorous or enjoyable experience. But as Nicholas Dagen Bloom writes in The Metropolitan Airport, the aerodrome on New York's southeastern edge was to embody a new kind of urban experience when it was founded in 1948. Known as Idlewild in its early years, the airport was indeed modern when it opened. Each airline built its own glamorous terminal: Pan Am had the Worldport, the postmodernist I.M. Pei designed "the Sundrome" for National Airlines, American Airlines featured a terminal with an enormous stained-glass window facing the outside world, as well as murals inside. These architectural masterpieces are gone, though JetBlue has saved the TWA Flight Center conceived by architect Eero Saarinen, a dance of white curves that manages to evoke flight via concrete. Someday, it will be a luxury hotel.

Between the demands of an automotive society, post-9/11 security strictures and the need to serve legions of peevish fliers, airports have become a combination of security bunker and shopping mall circa 1997: Mall of Homeland America. There are some respites: for example, the concourse in Charlotte Douglas, where you can lounge in a rocking chair, listen to live jazz piano and sip North Carolina wine; the art at Denver International. But spend an afternoon at Newark Liberty or Washington's Dulles, eating a greasy Sbarro's slice and watching CNN in a rigid bucket chair, and you will probably wish that you'd braved the bus, even if your final destination is Buenos Aires. If, as John D. Kasarda and Greg Lindsay argue in Aerotropolis, the 21st-century city will be centered on the airport, as the premodern city was centered around the port, then America badly needs a visionary who will make its airports great again.

Shortly after my first trip to Oakland International, I returned with my daughter. This time, the air museum was open. It looks better from the inside: a hangar filled with cool stuff. It would have been cooler if the stuff was less martial, but I can stomach a well-curated Top Gun fantasy. A frail-looking biplane withstood my 3-year-old's assault, I am relieved to report. Standing in front of a Pratt & Whitney turbine engine, she voiced only a single word, "Oy," and I could not tell if it was wonderment or rebuke. As in Holy crap, or This is a bit much, no?

When we inspected the flying boat from Raiders of the Lost Ark, she wanted to know if it could "go underwater." I explained that it could not, then tried to impress upon her the technical challenges of an amphibian takeoff and landing. She quickly lost interest, wandering toward the next plane. For all its wonders, aviation has yet to soar above the child's imagination.