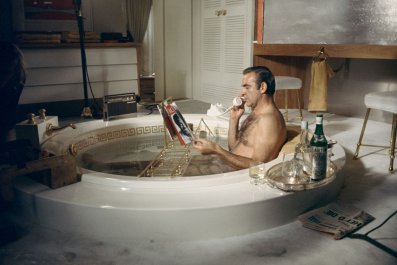

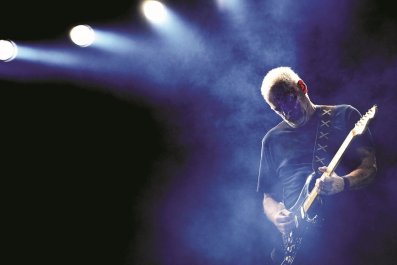

Carrie Brownstein: rocker, TV star, comedian, blogger—and now memoirist.

In her new book, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl, the Sleater-Kinney guitarist peels away any residual glamor and mythology of the riot grrrl movement and tells her tale of suburban upbringing and liberation. "This is a story of the ways I created a territory," Brownstein opens, though what follows is perhaps the least glamorous rock memoir you'll read all year. In vivid and funny vignettes, Brownstein recounts the youthful humiliations of beginning a career in music, and then the grueling trials of actually "making it," from inter-band squabbles and mid-tour hospital visits to sleepless nights spent on a foam mattress nicknamed "pube magnet." The author's success with the sketch show Portlandia, meanwhile, lurks just barely out of view.

Throughout the narrative—as Sleater-Kinney climbs from lo-fi experiment to thrilling and beloved rock band—music is conveyed as an agent of redemption, an escape from the monotony and anxieties of creative life. In a precious early scene, Brownstein writes about seeing Madonna's Like a Virgin tour in fifth grade. "It was a moment I'll never forget," she recalls, "a total elation that momentarily erased any outline of darkness."

On a rainy morning at the Carlton Hotel in New York City, Brownstein spoke to Newsweek about memoir-writing, airing her most uncomfortable band stories and why Sleater-Kinney is back for good.

So how did you come to write a memoir?

After Sleater-Kinney stopped playing music in 2006, I started writing for National Public Radio. Blog entries and a little bit of cultural criticism, talking a lot about the notion of fandom and how technology was changing that. Sometimes I would just write about bands I liked. I realized as I continued to do that—I think I worked there for about a year—that the most interesting pieces and the ones that the audience was most engaged with had myself as a narrator, drawing from my own experiences. Originally I conceived of a book that was more an extension of those pieces. It was going to be a little bit more [like] music criticism. But that just felt slightly false. It didn't seem like the story that I really should be telling or wanted to tell. I decided that I wanted to write about my journey, in terms of how I found music.

You started writing about Sleater-Kinney at about the same time you decided to get the band back together. Was that a strange experience?

There was a surreality to it. I felt like I was conjuring the ghost of this band that suddenly I resurrected, through the process of just combing through our history. It felt a little surreal, but also on a practical level just felt really normal. But it was a strange coincidence and, in a completely unplanned way, allowed the epilogue in the book, which I think made it less bleak at the end.

It was impressive that you kept the reunion a secret while writing the book.

We're still kind of stupefied by that. So many people knew. We were really careless about things.

You did such a good job of showing how unglamorous it is to be in a working band. Were you ever tempted to glamorize things a little more?

No, because I think it would have been so out-of-character for the tone that I had already set. I was talking to Kim Gordon, who had just written her memoir, Girl in a Band, last year. We were commiserating that often it's one of those professions where people's estimation of it is very otherworldly and magical and certainly opposite from the mundane. I feel like my book is just dragging it back down to earth. It really drives home the monotony of it. But I feel that context helps illustrate why the actual show, the actual performance, seems so magical. It's not because the entire day is a fairy tale. It's because it is about climbing out of the tedium.

Did you work with [Sleater-Kinney bandmates] Corin and Janet while capturing these old details?

I definitely did run things through Corin and Janet. Corin, especially—she looms so large in the book. I really wanted to make sure that she felt comfortable with it. So when we went back out on tour this year, I actually read parts of the book to her while we were sitting around her hotel room. I was like, "OK, I'm going to talk about when we were 18. Let me know if this is OK.…"

You talk a lot about fighting in the band. Was there anything that felt difficult to put on the page?

The intro to the book, which is the part that sets up the suspense of what's going to happen at the end, when we really just break up in Belgium. That was hard to write about. It had a very punishing quality to it. It did then, and even the way I was writing about it, it was very staccato. The prose became staccato. Everything started to feel like this series of punches again. We really never talked about that night again. It's not something that I processed or decompressed with Janet and Corin.

How has the No Cities to Love tour compared with that last tour?

Much kinder.

You've been around long enough that there are now many bands who grew up listening to Sleater-Kinney or wish they'd been around for riot grrrl.

When we went back out on tour at the beginning of this year, one thing that I really was excited about was it wasn't just our fans from the first time. A lot of people had just discovered us through [2015's] No Cities to Love. So we had a whole crop of young fans—16 to 25. And then we had people in their 30s who'd just missed us the first time around. In many cities, it was the new songs that people wanted to hear the most. That really assuaged all my fears of not wanting to do an album again. It was very wonderful to hear young people talk about relating to the lyrics and the music and the band, and that's half the reason you play, you know? That's why I listened to music when I was young—to have my own experience explained to me in a way I didn't feel capable of doing yet. To feel like we're providing that for someone else or giving them a launching point from which to explore their own creativity—that's great.

I imagine there are many people who know you from Portlandia and not the music.

Yeah. And this book is definitely not a jokey Portlandia thing, either. It's not like a humor book.

It must be weird to have two separate populations of fans.

It is a little strange. What I find very endearing about the Sleater-Kinney fans is that they're much more of a one-upmanship kind of crowd. Portlandia season five and No Cities to Love came out at about the same time this year. I was at an airport. This one couple came up to me and said, "Oh, I like Portlandia." "Thanks!" I turned and there was another couple and they said, "We like Sleater-Kinney!" The way they said it had such a supercilious tone. Part of it bothered me, but then I was also secretly proud, like, "Of course you took that tone!"

Do you see the book as a response to people who've always put gendered labels on your music?

I think it's an exploration of why those don't work and how that can feel. The people that want to put labels on you, I'm always curious what their motivation is. It's weird—when people put labels on you, it's almost like they assume that that's going to help you feel part of the world. I think if it's the wrong label, you feel further away from who you really are.

Has that continued with this current tour? You're no longer called an "all-women band" as much. It seems like now people talk about Sleater-Kinney as a great band, period.

Sometimes I think you just wear people down with longevity. You see it a lot. With a filmmaker, everyone wants to talk about, "Well, they're this kind of filmmaker, they're that kind of filmmaker." Then, like 10 films later: "Well, I guess we just have to think of them as a filmmaker." It's going through the laziness and the limitations of language that we all are confronted with.

Does this Sleater-Kinney tour feel like a one-off reunion or does it feel like you're back for good?

I feel like we're back for good in the sense that this band is part of the world and we'll make records at our own pace and outside of whatever cycle is being imposed upon music by other people. I love how PJ Harvey, you know, she'll put out a record at some point. It's kind of nice to be in that world, where people appreciate that you're there but it's not about frequency. For some artists, especially younger ones, frequency is very important. I don't think we're going to wait seven years. I'd like to put something out in the next couple of years.

What's your favorite music memoir?

I really did like Just Kids by Patti Smith.